The Climate Dilemma: Rescuing the Planet, Marginalizing the Poor [Part 1].

Caring for the planet is a noble cause. Hiding the effects that environmental policies would have on the lives of the poorest is, on the contrary, criminal.

[Note: this is the English version of the article originally written in Spanish and published in Historia Combustible.]

To provide context for this article, I'll use a concept introduced by Hans Rosling in his book Factfulness: the world's PIN is 1114. Out of the 7 billion people inhabiting our planet, 1 billion reside in the Americas, another billion in Europe, 1 billion in Africa, and the remaining 4 billion in Asia and Oceania.

Source: Gapminder

Any weighty analysis related to global issues should be filtered through data, which is what I expect to do in this article. We make judgments about global reality based on what we know; we apply a generalization bias, using parameters that don't apply elsewhere, and yet we assume them to be valid.

It is irrational (literally) to think about changing the world from a street in Stockholm, London, or Paris without considering that a little more than half of the population, equivalent to 4.1 billion people live in middle- or low-income countries.1

"I don't want you to hope. I want you to feel panic. I want you to feel the fear that I feel every day. And then I want you to act." - Greta Thunberg

Skolstrejk för klimatet2 has little relevance for those countries compared to a lack of food, health, employment, adequate infrastructure, personal safety, and education. What more panic is there to panic about?

Those of us who live in developed societies enjoy (yes, enjoy) the prosperity that has accumulated over the years, whether by making good decisions or good fortune. The average Swede consumes 59,927 kWh of energy per year, 84% more than the world average and about 50 times more than the average for low-income countries.

It also enjoys political stability, economic freedom, freedom of worship and expression, and has been able to complete about 19 years of schooling. Some, like Greta, have been fortunate enough to have the free time to protest against what they see as an insult to the planet. A free time that is only possible thanks to the use of fossil fuels. What for some is a threat; for others, it is their only tool towards a decent life.

Cancel me

On the other side of the protest are those of us who, without downplaying the importance of the climate issue, stop to question the feasibility of the proposals. If everything we have achieved in the last 70 years is because 3/4 of our energy sources are fossil fuels, how can we maintain our affluent living standards without using them?

You might think that the abundance of solar panels and wind towers would be part of the solution, that combined with technological advances in the field of batteries, we would be halfway to a 'clean' society.

Techno-optimism is a vision of the future that holds that technological progress will solve all the world's problems. However, this vision is inapplicable to places where the conditions for human life are precarious.

Places where it is impossible to have a refrigerator because electricity is unstable, where children have to collect materials to make and maintain a fire, transportation service is insufficient, if not non-existent, and per capita income is between one and ten dollars a day.

World income distribution:

Source: Our World in Data, Extreme poverty: How far have we come, and how far do we still have to go?

Therefore, there is a long way to go that must first converge (approach the upper-income levels, above 10US$ per day) and then be modified (improve to change).

According to the International Energy Agency:

[in 2023] Around 2.3 billion people lack access to clean cooking facilities and instead resort to the traditional use of solid biomass, kerosene, or coal as their primary cooking fuel. Household air pollution, mainly from cooking smoke, is linked to some 3.7 million premature deaths yearly. In the past, progress has been very limited compared to access to electricity.3

Is it acceptable to withhold access to electricity from millions of people because it is not produced from renewable energy?

Can it be considered ethical to ask developing nations to avoid using oil and coal, resources that were key to the industrialization of developed countries?

The big problem with these questions is that whoever asks them can be canceled, fast. Climate religion does not understand nuances, environmental totalitarianism as a steamroller.

Without ambiguity, I propose to answer the following question: What would be the effects of implementing climate measures to limit the increase in greenhouse gas emissions in the least favored sectors of developing countries?

My task, therefore, will be to try to do this with data.

I will divide this article into three parts:

The relationship growth, welfare, energy, how we got to this standard of living.

The claims of the environmentalists translated into reality.

What the reality would be like after applying the most extreme measures, the scenario where the radicals impose their vision.

Due to the article's length, I will publish one a week for the next three weeks. Here is the first one.

Part 1: Energy, Growth and Well-Being.

"Energy is the only universal currency. Without energy transformation, there is nothing."-Vaclav Smil

A dollar, a Euro, a Yen, or any other currency is a future right, the right to buy something later, which must be manufactured or acquired from another who will use the amount entered to buy other products or services in a never-ending cycle.

More money in circulation → greater demand for goods and services → greater use of materials and energy.

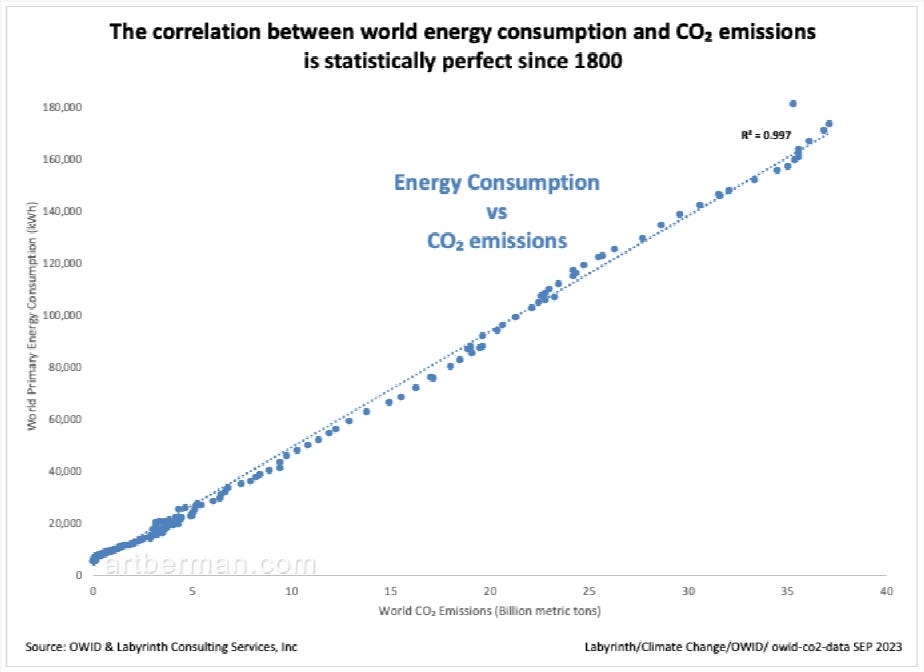

More energy in use → higher economic growth → higher CO2 emissions.

Source: THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM OF EMISSION REDUCTION, by Art Bertman.

During the second half of the 20th century, we experienced sustained growth in people's life expectancy4, not only in terms of the number of years they could live but also in the comforts to which they had access as a result of cheaper goods and services. It was when a thriving middle class emerged in the West, and its rise was reflected in what it could buy: vehicles, household appliances, and, of course, a house of considerable size.

I stop here because, in keeping with reality, not all countries in the world and even in the West experienced this bonanza; however, like someone who looks at a piece of cake from the window and wishes to eat it, the example that American society gave to the world was the model to be copied not only by other countries in the hemisphere but also by those who, once the socialist bloc in Eastern Europe fell, followed in its footsteps.

This implied that welfare would directly result from associating 'freedom' with 'purchasing power.’

As I have already mentioned, to have more, you have to produce more, and more production makes the economy grow. The economy's growth is the utmost milestone a politician can offer his voters since more is to be shared. It is, therefore, logical and pertinent to affirm that -having more- is a fundamental part of the discourse that attracts people and their votes; it is what convinces them.

The economy is a cloud of transactions from which labor, capital, and technology come together to increase the value of something. From the seed, the flour is made; from the flour, the bread, and from the bread, the pizza. Money is the lubricant of all these operations where 'things' change hands.

In economics, two types of growth can be distinguished: real growth and monetary growth.

Real growth takes place in the tangible world, that is, in producing objects and services that can be seen, touched, received, offered, and enjoyed. On the other hand, monetary growth occurs in money, which is a symbol of value that has no intrinsic value, only an indicator that can have a greater or lesser consideration in the form of products or services.

Money borrowed from the bank in the form of credit has to be repaid with interest because it is supposed to be used to create more things. In this way, credit helps drive real growth in the economy.

Therefore, the constant promise of progress is something we long to hear and an experience we hope to live personally and see reflected nationally. It represents the conversion of effort into reward and the way to compensate for the risks taken through the gains made. It means the hope that our children will live in better conditions than we do, acting as a positive feedback loop.

It is also fertile ground for the not-so-good things such as financial speculation, income inequality, capital accumulation, protectionism, and the notion of "too big to fail,” among other phenomena related to the movement of capital that strengthen existing power.

So, it is not simply replacing a gasoline car with an electric car or a coal plant with wind turbines. The transformation of energy sources implies a fundamental change in civilization itself. Without this transformation, conflict, famine, and disease could lead to extinction before the dreaded changes in global temperature.

Note: The pyramid of energy needs, represents the minimum EROI (Energy Return on Investment) required for conventional oil at the wellhead to perform various energy tasks necessary for civilization5.

The economic activity we see with the naked eye is only part of the story. Below the waterline, millions of interactions are not visible to the general public.

We must look beyond what we see to understand how the world works. We must look for what is hidden, what is unseen.

One of the great truths beneath the floating edge of the iceberg is peace. A peaceful planet is only possible as long as marginal income is growing so that people and countries have a little more tomorrow than they do today, and if not, the prospect of having it is attainable. In the words of Yuval Noah Harari, "Tolerance is not a trademark of the Sapiens"6, we live in the most peaceful era since we populated the earth, and it is no coincidence that it is also the era in which we managed to have abundant amounts of energy, which allowed us to lighten our work and, of course, to cover our inefficiencies in other areas.

Throughout history, power was based on the possession of energy, whether in the form of slave labor, tilling the soil, or transforming steam into work.

Seen in aggregate, at the country level, generally, the greater the energy use, the more powerful, the more complex its relationships, the more productive it is. The same is true in the opposite direction; in most cases, less development goes hand in hand with less energy consumption. This is not an axiom but applies to most cases that can be consulted.

It is clearly expressed in the following graph:

In its most basic form, energy allows us to have a structured, predictable life, with the possibility of planning for the future and going for it. It is what heats our homes, cooks our food, lights our streets, and allows us to move. A deficit of it would make our lives very different.

Gas, oil, and coal have different uses; they are not interchangeable at will with renewable energies (and not even among them). Minimizing their use in certain activities is possible if we understand it will have consequences.

In the current circumstances, cutting the use of fossil energies would bring about degrowth and conflict, not because there is no good reason behind it -the care of the planet- but because any change made by reducing the flow of energy consumed can lead to poverty for billions of people if it is poorly executed.

The adaptive capacity of a developed country is not the same as that of a country whose specialization is low and whose economy is dependent on the extraction of raw materials.

Graph note: Oil, coal, and gas account for 76.71% of energy consumption as primary sources.

It doesn't take a very complex exercise to prove it. Here are some facts:

99% of food transportation fleets use diesel as fuel.

99.9% of aviation fuel is fossil fuel.

80% of fertilizers come from natural gas processing.7

70% of steel production uses coal as an energy source.8

60% of medical surgical equipment is made from plastic.

More than 80% of packaging and preservation materials are made from plastic.

60% of the world's electricity generation is made from natural gas.

The transition to renewable energy sources will depend on the nature of each country's productive apparatus; it will be much easier for those whose economy is based more on services than those with a more significant industrial or agricultural component. Not to mention that sunlight and wind are itinerant, and there is no capacity to accumulate energy in the quantity and power necessary to replace concentrated energy in the way fossil fuel options are presented.

In addition, if we could obtain all the energy we need from the wind, the sun, the sea, and any other renewable source, we would be facing a paradox in which the consumption of fossil fuels would continue to occur. This is called the Jevons Paradox.

W. Stanley Jevons was an English economist who realized that the more efficient energy used, the more consumed it. If there were a non-polluting substitute for oil, for example, more oil would still be consumed because its price would drop due to its greater availability.

As with any product, the quantity sold increases when its price decreases.

There is also a moral aspect. How can we prohibit developing countries from using the energy that allowed developed countries to reach such a level in the past? No one denies the benefits of renewable energy in electricity generation. Still, the infrastructure needed to make it a feasible option in countries in Southeast Asia, Southern Africa, or Latin America would require investments of billions of dollars that could be channeled to other initiatives equally or even more necessary than environmental care.

This is described in detail by Bjørn Lomborg in his latest book: Best Things First. The 12 most efficient solutions for the world's poorest and our global SDG pledges. Among the causes he mentions are the fight against malaria and tuberculosis and assistance to pregnant women and newborns, all of which would have a tangible impact on the communities that suffer from them.

24-hour deliveries, full supermarkets

We often take for granted that devices and systems work because we see them working, but we don't stop to think about how this is possible. One example of this is freight transport.

The relationship between diesel, truck, and load is direct and obvious, but there is a cost logic that we do not see at first glance. The price of the energy used to transport the goods must be lower than the value of the loads. If it were not, it would not make economic sense to move any product.

One of the arguments most often used by environmentalists is that the oil industry is subsidized, and they are right. Not only through tax exemptions, subsidies, or the intensive use of infrastructure built with everyone's taxes (it is not the only one either; almost all companies use public goods), but it is also accurate to affirm that agriculture is subsidized by oil.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global fossil fuel subsidies will reach a record $7 trillion in 2022, representing 7.1% of global GDP.9

It is impossible to feed 7 billion people without the use of a highly concentrated, transportable, ready-to-use energy source such as gasoline, diesel, kerosene, and other distillates used in the various stages of cultivation, from land preparation through planting, fertilization, harvesting, refrigeration, packaging and final distribution. Each calorie of food consumed by us humans requires the use of between 7 and 10 calories from hydrocarbons (machinery, fertilizers, transportation).10

Without fossil fuel subsidies, there would not be enough food. Convenient or not, morally acceptable or not, this is the current situation.

"The energy of fossil fuels is the food of food."-Alex Epstein, The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels.

Indeed, the relationship between energy use and well-being is not linear. Well-being is a subjective concept that depends on personal and cultural factors. However, if one measures economic growth, a more objective concept, the correlation between energy use and economic growth is closer. This means that, in general, countries that consume more energy also grow more economically.

The growth of a country generally implies an increase in the economy's size; the sum of products and services is understood to increase, corporate profits grow, employment grows, and the government obtains more resources through taxation. The repetition of this cycle for decades has culminated in the strengthening of middle classes, academically prepared and politically active, which have been promoters of equality laws, social benefits, and inclusion, among others. This is only possible because the growing productivity in using one of the resources -energy- has allowed more free time to study, prepare oneself, and cultivate other areas of being that were not previously an issue.

If we move to developing countries, fossil fuels play a fundamental role. In producing countries, they represent most of their fiscal revenues (70% on average for countries in the Persian Gulf)11. The sale of crude oil, gas, and coal generates foreign exchange, allowing them to have a less lousy balance of payments. This generates government employment, maintaining social cohesion in highly volatile countries.

In the case of other developing but not producing countries, it represents the most expeditious way to boost their industry, light their streets, and move passengers and cargo. It is the capacity to plant the fields, extract minerals, and build infrastructure.

Wind, sun, and biofuels cannot concentrate the energy needed to melt steel or fly an airplane. That much is clear.

In the words of Gail Tverberg12:

Green energy sounds attractive, but it is terribly limited in what it can do. Green energy can't run farm machinery. It can't make new wind turbines or solar panels. Green energy cannot exist without fossil fuels. It is simply a supplement to the current system.

Any action taken to reduce the supply of fossil fuels or penalize their use will negatively affect people engaged in the lowest-paid activities with the fewest options for alternative income, such as agricultural laborers, construction workers, domestic services, and informal workers.

Efforts should instead focus on increasing per capita energy use in poor countries. Either by giving them access to gas or coal-backed electricity or providing sufficiently safe and well-built roads -among other many feasible options- to boost the local economy so that investment flows to these 'virgin' places. It would be irresponsible to try our luck to transition from little available energy to renewable sources without having the same opportunity that countries now considered developed had to use billions of barrels of oil while climbing the economic growth curve.

"It is not realistic to completely phase out fossil fuel energy" - Xie Zhenhua, China's special envoy to COP28.

Footnotes:

https://fridaysforfuture.se/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421513006447

https://www.yara.com/crop-nutrition/crop-and-agronomy-knowledge/how-we-make-our-fertilizer/#:~:text=Natural%20gas%20fertilizer%20production%20is,for%20heating%20and%20electricity%20production

https://www.futurecoal.org/coal-facts/coal-steel/#:~:text=Coal%20%26%20steel%20Steel%20is,Quick%20Links

https://ourfiniteworld.com/