Oil, Debt, and Influence: China's Grip on Venezuela

Summary: This article presents conclusions from analyzing China and Venezuela's political and energy relationship over the past 20 years. It begins by examining China's transition from a low-growth economy and energy exporter to a global development engine with high natural resource consumption. Then, it explores the motivations behind the 5th Republic politicians' attempts to meet China's oil demand without considering factors such as distance, transportation methods, associated costs, and production efficiency. Regrettably, as of September 2023, the results have been disastrous, marking yet another failure of the revolution.

Part 1 - China: A story of rise, dominance, and the search for resources

No more, Comrade Mao

When analyzing China's relationship with another country, it is essential to consider the changes in their bilateral relationship over the past 30 years. China's rapid economic growth has transformed from a subordinate and overshadowed nation into a pioneering leader.

After years of cultural revolution, the government in Beijing recognized that the only way to improve the living standards of over a billion people was through a combination of political and economic measures. They adopted a Leninist-style political control system and implemented a free-market economy following the reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s.

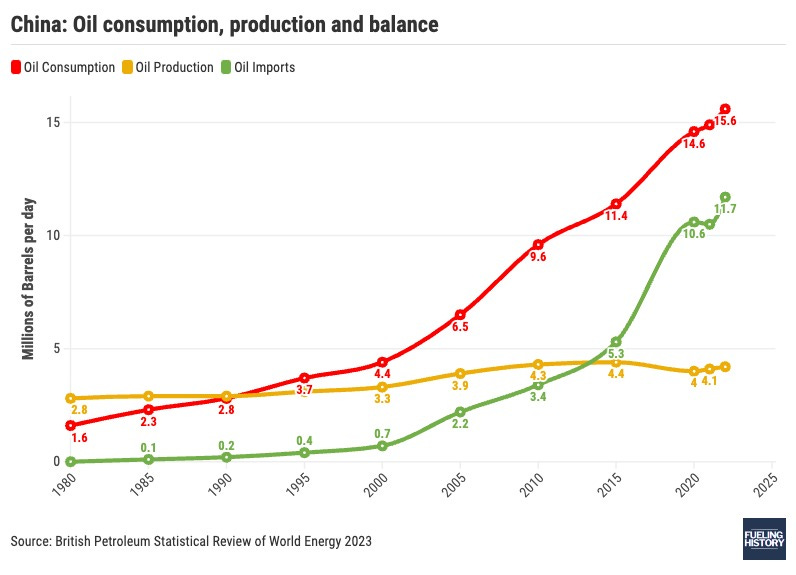

By 1983, China was a net oil exporter and held a prominent position on the global energy stage, even potentially being able to join OPEC, the entity controlling global energy at that time.

The economic growth driven by these reforms directly impacted energy consumption. According to a study by the World Bank, there is a fairly high statistical correlation between economic growth and energy consumption, with a value of 0.81. However, improving the quality of life for the population also had a negative consequence: China became dependent on international energy markets, jeopardizing its security. (Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2023)

A few years earlier, between 1973 and 1974, Arab countries had imposed an oil embargo on the United States in response to its support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. At that time, it was evident to any sensible person that depending on others was not something to be taken lightly, especially because without energy, there is nothing.

In this context, an important part of the Communist Party of China's policy is implemented: geopolitics oriented towards guaranteeing the supply of resources they need through quick partnerships with countries of interest. I remember talking to a friend who is part of a government in sub-Saharan Africa, and he told me that over time, the authorities in his country concluded that it was much easier to deal with China than with the United States. Although both countries sought to benefit from the aid they provided, the Chinese way of acting was carefree, fast, and without protocol, summed up in a suitcase full of cash.

The success of the resource-seeking policy lies in China's ability to enter anywhere, regardless of conflicts, instability, or adverse weather conditions. If there is a signed agreement, hundreds or thousands of Chinese citizens will arrive to carry out the necessary tasks, whether supervising agricultural production or extracting oil from a field in the middle of nowhere.

The Hungry Dragon

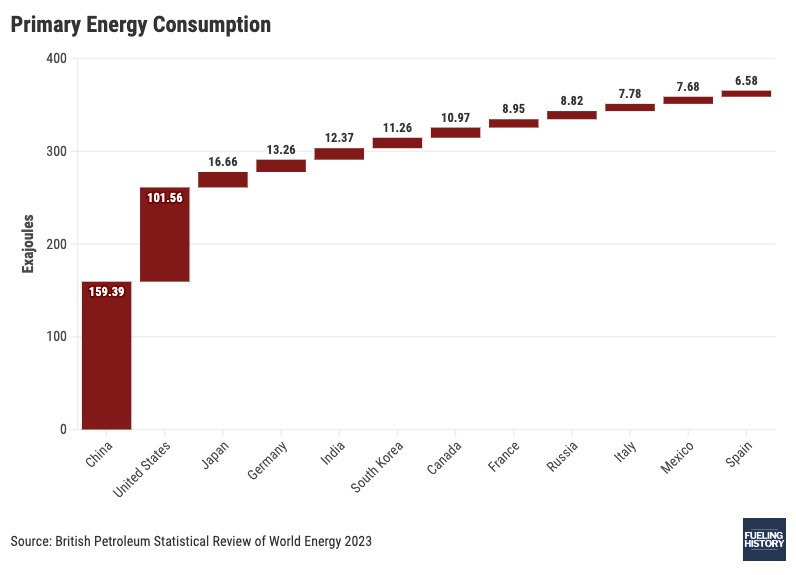

China consumes a substantial amount of energy, approximately 157.65 exajoules (EJ), equivalent to 277.8 terawatt hours (TWh). However, here's the fascinating part: the majority of this energy, around 81.3%, is generated domestically. The remaining 18.7% is sourced from other countries.

In 2022, China generated a significant portion of its energy, specifically 128.29 EJ. Here's the breakdown:

Coal: 70.7%

Oil: 13.8%

Natural gas: 10.8%

Hydropower: 9.4%

Nuclear power: 3%

And in terms of its imported energy in 2022, here’s the breakdown:

Coal: 58.3%

Oil: 37.9%

Natural gas: 3.8%

In simple terms, China primarily generates its energy but also relies on other countries, particularly for coal and oil. It's akin to a combination of homemade meals and takeout to ensure a continuous power supply and keep the machinery running.

One of the significant peculiarities of China is that it has managed to play a three-way game. As the world's factory, it accumulated vast surpluses of dollars from its current account balance. For an export-based economy, one of the premises of its monetary policy is to artificially maintain a low exchange rate by devaluing its currency so that parity favors the purchase of products by other countries.

This may seem contradictory, as a country with extensive industrial capacity that is dedicated to the production of all kinds of items, in addition to satisfying the progressive increase in demand from its inhabitants (no less than a billion people), more resources have to be allocated to the purchase of energy.

However, despite being divergent forces, they are not a zero-sum game. The difference between the cost of production and the selling price of what is produced in China, multiplied by its vast industrial capacity, understood in basic economics as PXQ, allowed the profit rates to cover energy purchases comfortably.

For example, in 2021, China had a trade surplus of $396.5 billion with the United States. This means that China exported $396.5 billion more worth of goods to the United States than it imported from the United States. China's energy import bill in 2021 was $286.8 billion. This means China's trade surplus with the United States was more than enough to cover its energy import bill. This oversimplifies the complex relationships involved in the country's trade balance, but at the same time, it is a valid notion supported by data.

Equal to equal

One of the consequences of economic growth is the robustness of the system itself. Generating income causes the exchange rate to be pressured to equalize with other currencies. China has relied on a competitive advantage for almost four decades: low wages. Putting aside morality and viewing it as a productive factor, cheap labor boosts competitiveness. If we closely examine China's case, it has in its more than one billion inhabitants an almost unlimited resource to offer, inelastic by nature (the employment rate will not change in response to wage variations because there is too much supply).

Monetarily, it is known that the Chinese government has pursued a structural policy of artificially devaluing its currency through abundant domestic credit. This strategy poses a long-term danger of creating consumption or real estate bubbles similar to the one currently experienced with Evergrande.

This is when economists use their tools to compare apples to apples, standardizing the data to understand where a country is heading. The best measure to comprehend this is the gross domestic product, filtered by purchasing power parity. Simply put, how many goods and services can be purchased with one dollar in China compared to another country, let's say the United States.

The gross domestic product measured by purchasing power parity has evolved as follows:

The following graph shows the GDP PPP gap between China and the US over the last 40 years:

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook

China has not only experienced significant growth, but it has also liberalized its trade relationship with the world and modernized the country through substantial investment in infrastructure. This has resulted in an aggregate demand and economy size that equals or surpasses countries with a long tradition, such as the United States, Germany, Japan, France, and Australia.

The offensive for resources

Beijing has articulated different ways of influencing the world. A country that devours resources and is deficient in almost all the inputs its economy uses (except for labor and capital) has to develop a plan to bring countries that can provide them with such resources into its orbit.

This is how China, for several decades, has fostered international assistance through the China Development Bank by providing lines of credit to countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. All of them, the recipients of the aid, have a similar profile: developing economies belonging to the "Global South," with a surplus in natural resources, with weak governments eager to avoid going through multilateral institutions created in the second half of the 20th century, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Another effective way to make friends is through direct investment in joint development plans. This is how joint ventures with Russia for oil exploitation in fields that would have remained unproductive due to lack of funds become a source of crude oil that will ultimately drive the Chinese industry forward.

Among the numerous ventures China has established in the last 20 to 30 years, there is evidence indicating that this game is one of the core objectives of the country and its government officials.

PetroChina has investments in oil fields in more than 30 countries, including Kazakhstan, Russia, and Angola.

Sinopec has investments in oil fields in over 20 countries, including Venezuela, Iran, and Algeria.

CNOOC has investments in oil fields in over 10 countries, including Brazil, Canada, and Nigeria.

In 2013, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) acquired Canada's Nexen Energy for $15.1 billion, marking the largest Chinese acquisition of a foreign company at that time.

In 2009, China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) acquired Swiss oil and gas company Addax Petroleum for $7.2 billion.

In 2005, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) acquired Kazakhstan's KazMunaiGas Exploration and Production (KMG EP) for $5.7 billion.

The main difference between China and dominant powers such as the United Kingdom, France, or the United States regarding oil-rich areas like the Middle East lies in authentic "soft power.” Both in official and informal versions, Beijing has chosen to find a way to go unnoticed, enter through the back door without attracting attention, and justify its presence based on the rights we all have on this planet. China utilizes the concept of multipolarity as a basis for its actions.

According to the country's Energy Policy 2012:

"China did not, does not, and will not pose any threat to the world's energy security. Abiding by the principles of equality, reciprocity, and mutual benefit, it will further strengthen its cooperation with other energy-producing and consuming countries and international energy organizations and work together with them to promote sustainable energy development worldwide. It will strive to maintain stability in the international energy market and energy prices, secure international energy transportation routes, and make necessary contributions to safeguarding international energy security and addressing global climate change."

China has shown significant interest, both historically and currently, in acquiring resources and promoting its manufactured products. With a market of hundreds of millions of potential customers, it is a mutually beneficial business opportunity. Furthermore, many loan agreements stipulate that Chinese companies must carry out the projects, minimizing the risk of loss.

PART 2 - Venezuela, an upside-down story, from glory to disaster.

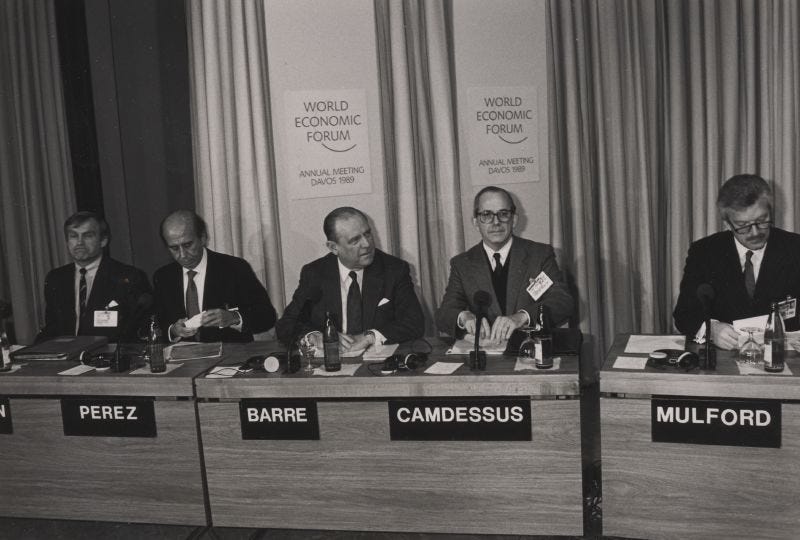

Carlos Andrés Pérez, Venezuelan president at the WEF in Davos, a place that has never been visited by a Venezuelan democratic president ever since.

A Three-Act Play:

The history of Venezuela can be divided in several ways, but for this analysis, I will consider three stages. The first one spans from Columbus' arrival in 1498 to 1913. The second one starts with the discovery of oil in 1913. The third one corresponds to the arrival of the Socialist Revolution and its impact on the oil industry from 1998 to the present day.

The Land of Grace was discovered in August 1498 by Christopher Columbus on his third voyage. At that time, no one imagined that this piece of land, besides having beautiful beaches, would become the largest oil reserve in the world in the early 2000s. But Venezuela, that beautiful country, is characterized by its contrasts, and this is just one of them.

To keep the history from becoming too extensive, it is enough to say that Venezuela was an agricultural territory for approximately 415 years. It was designated as a Captaincy General due to its lesser importance than other territories that became Viceroyalties. In these Viceroyalties, wealth flowed in the form of precious metals. Luck (or lack thereof, depending on who analyzes it) meant that Venezuela not only could produce oil but also floated in it.

Venezuela experienced its highest economic growth rate between 1948 and 1973, averaging over 6% annual growth. This was fueled by rapid industrialization and urbanization, driven by the country's oil wealth. Venezuela's GDP per capita grew even faster, at an average rate of over 7% yearly. During this time, the country was one of the most prosperous countries in Latin America and was even considered a developed country by some standards.

In the 1960s, oil exploitation depended on technical assistance from the United States. For the political leadership of Venezuela, it was a period of vassalage, which is why, by the late 1970s, the industry was nationalized, becoming entirely in the hands of national operators. From that moment on, the country proudly developed an industry that would be the pillar of the expected development; it was Saudi Venezuela.

But as is widely known, there is the "paradox of abundance" or the "resource curse." Either of the two views, half-empty glass or half-full glass, serves to explain that, indeed, a country with so much wealth would have incurred sizeable current account deficits during the ten years following nationalization. Among the main reasons for this was the lack of productivity in the rest of the economy, subsidized by oil revenues. The government received enormous resources in the form of taxes from oil sales. Both fiscal and monetary policies were expansionary, indicating an unrestricted abundance in this prosperous nation.

By maintaining a fixed exchange rate policy between the bolivar, the national currency, and the dollar despite the immense differences in productivity, the speed at which the government was getting into debt, and the situation caused by the fall in oil prices after reaching highs during the 70s, the 80s witnessed a decline in the quality of life in Venezuela that has not stopped until today, 2023.

Two psychological factors must be analyzed to better understand the attack and deterioration of the oil industry in the country. Firstly, oil companies in producing countries employ between 1% and 10% of the economically active population globally. In the case of Venezuela, historically, this percentage has been around 1% or 2%. This generated that 98% of the population depended in some way on oil subsidies, creating the perception that working in the oil industry was almost impossible and was associated with the ruling elites, generating resentment in the excluded classes. That is why, once Hugo Chávez and his revolution created the most significant change in the industry, even greater than nationalization, nowadays PDVSA Petróleos de Venezuela exports less than 80% of what it was once able to sell to other countries, a disastrous result considering that 95% of the country's income comes precisely from -oil sales-.

The Quantitative Leap

In 1956, Marion King Hubbert proposed the concept of "Peak Oil," which predicted that by the mid-1960s to 1970, the world would reach its maximum capacity for oil production and that, from then on, there would be diminishing returns and an excessive increase in hydrocarbon prices. Although this idea never generated massive concern among large multinational companies dedicated to the business, it opened the door to accelerate the discovery of oil fields and to consider unconventional sources as valid alternatives to obtain the energy that the planet consumed voraciously.

Hubbert's 1956 peak oil graph. Source: M. King Hubbert, ''Nuclear Energy and Fossil Fuels,'' Shell Development Company, Publication No. 95, reprinted from Drilling and Production Practice (1956).

The window opened decade after decade to allow the entry of higher API-grade crudes, which have higher extraction costs within the accepted range. This, along with the improvement of prospecting and extraction technology, has allowed the inclusion of reservoirs such as the Orinoco bitumen belt, the Canadian Tar Sands, offshore wells off the coast of Brazil, and even deposits that were previously considered non-viable but are now exploitable thanks to hydraulic fracturing (fracking), in the reserves equation. This has increased the availability of crude oil to levels ten times higher, going from 182 billion barrels to 1.8 trillion in 2023.

I must emphasize that here, I am briefly referring to the gradations of oil, API grades, and the Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI), concepts that require a complete publication, especially the latter.

In 1998, Hugo Chávez, a retired military officer forgiven for a failed coup d'état, won the presidential elections in Venezuela. This was a typical occurrence in Venezuela. The country not only desired a radical change in direction but also chose a military officer to bring about that change. Interestingly, out of the 40 presidents that Venezuela has had, 21 have been military officers, while 19 have been civilians. However, the military officers have spent more time in power, averaging 1665 days compared to the civilians' average of 915 days. What initially appeared to be a revolution was, in fact, more of a return to a relaxed internal control and the dismantling of the oil state that was established with the nationalization of the industry in 1978.

During the early years of the 21st century, oil prices experienced a sharp increase driven by the growth in China's consumption and by greater and better coordination among producing countries, who had seen the selling price of their primary export product reach levels of $11 per barrel in 1998.

During a live speech, Hugo Chávez announced that Venezuela had become the country with the largest oil reserves in the world, estimated at 297 billion barrels. Although there were downward revisions by OPEC, putting the reserves at 211 billion barrels, the final number was eventually established at 303 billion barrels, according to BP's Statistical Review of World Energy in 2019. Despite the variations in the figures, the truth is that the number is considerably large and attractive for a country like China for various reasons besides the obvious.

The Bolivarian revolution, with its Marxist inclination, took advantage of two very market-oriented circumstances to fill its pockets - and those of its acolytes. The first is, as shown in the graph, the sustained increase in the selling price of the Venezuelan oil basket, going from just over 11 USD to 109.50 in 2012. The fiscal income of the government - not the country - multiplied by 10 without any increase in productivity or improvement in the conditions of public or private companies. It was like the story of Moses leading the Jews to the promised land, manna from heaven.

China enters the scene

The big question to ask here is, why did Venezuela choose to discourage the sale of its oil to its natural market, the United States, in favor of a buyer with whom there was no significant tradition of business, who is very far away, and whose culture is so different? The answer is easy money.

China understood that the way to enter countries is with hot money, few questions, and a lot of discretion. These disbursements have a political component, the cost of Beijing's expansion of influence on other continents, and another component that is dedicated to indebting countries, the kind of debt that cannot be forgiven and must be repaid no matter what.

Someone I know, who lived and did business in China for over 20 years, once told me a phrase I will never forget: "The religion of the Chinese is money," and it makes perfect sense. Whether through militant Marxism or Mao's cultural revolution (Marxism with local nuances), both currents, although related, do not equate money with religion.

China, through a detailed operation - yes, meticulous, clear, and specific - combined its foreign policy defined by the State Council with the immense resources available from the People's Bank of China, the institution that holds the country's positive current account balances, as well as its investments, securities, bonds, and assets abroad. To Venezuela, an estimated 50 billion dollars were allocated, which were used for direct money transfers to the population through "missions," construction of infrastructure (most of which never saw the light of day because the funds were stolen), military spending on equipment from the club of new friendly countries, and payment of the already contracted debt with China at a lower value. The result was a total disaster that did not improve the quality of life or productivity of the country.

This is how a story begins conceived for the failure of one of the parties, either by action or omission. Venezuela aligned itself with left-wing, anti-establishment governments, thinking it could rely on the collective strength of emerging economies as allies, namely China, Turkey, Iran, Argentina, Brazil, and Russia. But what seemed like a good plan on paper ended up gradually isolating Venezuela from international forums, relegating it to a lower-tier country and causing its once thriving economy to reach levels of impoverishment comparable to war-torn African republics.

The underlying thread takes us down a clear path: the deterioration of governance levels in the country, supported not only by a radical change in policy but also by aligning with countries that could hardly contribute dynamism to Venezuela's economy. This led to an internal and external crisis from which it has been unable to recover.

If you have been paying attention so far, you may have realized that this is a déjà vu of what happened in the country 40 or 50 years ago, but instead of China, it was with the United States. The scenario is the same: a country with extraordinary hydrocarbon reserves, a country with growing consumption and an oil thirst, a disproportionate increase in the selling price of a barrel, an increase in fiscal income that is wasted and ends up further indebting Venezuela despite being in the midst of a boom. The world turned upside down.

During Hu Jintao's presidency, China sought to strengthen relations with the rest of the world through the policy of "Harmonious World". At first glance, this did not seem unreasonable after the abrupt fall of communism in 1989 and the unipolarity that had taken hold of the planet, led by the United States. In the 1990s, the consequences of the invasion of Iraq, the long war in Afghanistan, the polarization between Israel and Iran, and the subsequent proliferation of terrorist threats led to the belief that they needed to, at least reconsider the course of relations between countries. What is not said, at least not so explicitly, is that as we know, governments do not have friends but interests, and China, far from being an exception, has understood in most cases that assisting countries with institutional weakness will leave them in an advantageous position when claiming repayment of the debts incurred. Debtor countries cannot be rescued from that predicament.

While Venezuela decided to distance itself from Washington, the United States, in parallel, did everything possible to damage its image after the September 11 attacks. The consequences of these attacks led Venezuela (and many others) to choose between supporting the intervention and militarism promoted by George W. Bush or staying on the sidelines and seeking support elsewhere, less reactionary and less inquisitive.

Far, costly, and operationally complicated

Turning the pipeline around

During my time in school, I was an average student in most subjects. I passed some with ease, while others not so much. The only subject I struggled with was physics. I studied hard, driven by my mother's threats that my life would be miserable if I didn't get an outstanding grade on the exam. I mastered the content I was taught and became genuinely interested in the immutable laws of Newtonian physics. I mention all this to emphasize that distances and time, in physical terms, are unchangeable. While we can change our perception of time and space through psychology, getting used to something, the feeling of waiting or location can vary depending on the person evaluating it. However, indeed, China is farther away from Venezuela than the United States. Therefore, it was necessary to rethink everything that was known to date about oil delivery.

All this new structure and way of doing business would be framed within a vertical integration of China's state-owned oil company CNPC (China National Petroleum Company) and PDVSA (Petroleum of Venezuela). It would not be limited to a straightforward buyer-seller relationship and repayment of loans but rather a joint effort in which they would accompany each other from extraction to refining, obviously including transportation. That is the crux of the matter.

The Panama Canal is one of the marvels of modern engineering, not only for what it required in human and material terms during its construction but also for the incalculable resources it has saved in terms of costs and transportation time between the Pacific and the Atlantic. Being a critical infrastructure of top geostrategic importance, it was under the administration of the United States for over 80 years until its administration was reverted to the Republic of Panama in 2000. I remember that when I lived in Panama in 2008, it was the first time a Russian war frigate transited through the Canal, an event that did not go unnoticed and was a reminder of the Cold War. Commercializing through this corridor without being under the Western influence of power was practically impossible, not to say completely impossible.

In 2005, the first of the ideas was presented, which, spoiler alert, none of them were carried out. This consisted of taking an operational pipeline and changing its functionality. A few months ago, while reviewing the state of oil infrastructure in Latin America, I came across a study conducted to increase the capacity of the Trans-Panama pipeline. Furthermore, reversing its original direction, which had been conceived to receive oil from Alaska and use it to supply the refineries on the East Coast, receiving oil extracted in Venezuela and taking it to China. This piqued my curiosity and was why I started researching for this article.

According to Roy Neressian from the Center for Energy, Marine Transportation, and Public Policy at Columbia University: "The round trip voyage from Venezuela to U.S. Gulf ports is 3,600 miles. The round trip voyage to China (via the Panama Canal) is 17,000 miles, or nearly 5 times farther. The most economic method of shipping Venezuelan crude to the U.S. Gulf is in an 'Aframax' class of tanker — i.e., one between 80,000 and 120,000 deadweight tons. Aframax vessels in the Venezuela/U.S. Gulf trade carry cargos of around 70,000 tons — i.e., less than their full carrying capacity — because of draft limitations (shallow water depth) in Lake Maracaibo (the waterway surrounding Venezuela’s principal crude loading ports) and in U.S. Gulf ports. The largest cargo that can be carried through the Panama Canal is around 55,000 tons because of beam (vessel width) and draft limitations that restrict vessel capacity and cargo size. Transiting the Panama Canal involves a toll, which would add to the cost of transportation to China. Venezuelan crude oil exports to China on Panamax tankers via the Panama Canal would cost five or more times as much as shipping the same crude to the U.S. Gulf"

Based on this, it was necessary to find a way to reduce transit times and costs by incorporating a pipeline section into the transportation mix. The solution consisted of three parts: 1. Using Panamax ships from Venezuela to Chiriquí Grande, 2. Crossing the isthmus through the pipeline, 3. Using VLCC ships from Puerto Armuelles to China. Beyond the solution's viability, I want to emphasize the effort required to bring oil to a non-traditional market. The transportation alone from Venezuela to Panama and the cost of using the pipeline would equal the cost of the entire route from Venezuela to the United States, which had been used for over 80 years.

Despite the costs, higher than those accustomed to operations destined for refineries in the Gulf of Mexico, as long as the oil price was high, it was financially feasible. Not efficient, but feasible.

This proposal encountered the Venezuelan government's inability to execute one of the thousands of projects the 21st-century revolution set out to carry out. I understand that The geopolitical game limited the Venezuelan government's ability to negotiate with the government of Mireya Moscoso in Panama, which was closer to the United States than the multipolar order. It is worth noting that in 2008, BP announced an agreement that emulated the originally proposed conditions by Venezuela, reversing the flow of oil in an Atlantic-to-Pacific direction to transport crude oil from Colombia to different markets in Asia.

The attempts continued, and in 2013, PetroChina tried to buy the assets and pass Venezuelan oil through it, not only owning the pipeline but also the crude storage facilities at one of its ends, according to Energy Intelligence.

The company aimed to enhance the economics and security of its overseas crude supply, as well as increase Venezuelan imports. The talks involved Petroterminal de Panama (PTP), the owner and operator of the pipeline system, as well as the Panama government, oil trader Gunvor, and New York-based Northville Industries. PetroChina was also interested in acquiring the storage facilities at both ends of the pipeline, which had a total capacity of 14 million barrels. The Trans-Isthmian pipeline, which spanned 131 kilometers, operated in reverse mode, transporting oil from the Atlantic terminal to the Pacific coast. The purchase of the pipeline would have allowed PetroChina to increase its crude shipments from Venezuela, as most of China's imports of Venezuelan crude currently took the longer route around Africa. The Panama Canal's restrictions on tanker size limited the flow of crude, but there were plans for expansion. This potential Chinese ownership of the pipeline raised concerns in the United States, given the historical strategic relationship between the two countries. However, with the changing dynamics of crude trade flows, it was possible that in the future, US crude could be transported through the Trans-Isthmian pipeline to Asia if oil export restrictions were amended.1

A Three-Legged Table

The latest adventure occurred in 2006 with the announcement in Maracaibo of an oil pipeline that would start in Venezuela, pass through Colombia, and end in Panama. Venezuela would fully cover the investment for the project.

Looking at 2006 from the perspective of 2023, I can understand that many planned projects are not carried out due to unforeseen circumstances. And why do I mention the year 2023? To date, it is still unknown who was responsible for the destruction of Nordstream 2, a vital infrastructure for the German industrial complex.

Extrapolating the facts, it is very likely that the politics of blocs have worked against Venezuela, especially if this oil pipeline was supposed to go through two traditional partners of the United States.

Here, I introduce another factor, which is why I talk about three legs. The first is the energy relationship between China and Venezuela; the second is the politics of blocs with countries in the region, where the influence of the United States is crucial, and the third is the expansive monetary policy at a global level.

This relationship is based on the fact that as China grows, it needs more energy without many complications. However, we cannot overlook that after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, where austerity measures were implemented - restricting aid to institutions in trouble, such as banks and companies - (although there were bailouts, they were not on the same scale as those we will witness later with the COVID crisis), the monetary policy adopted by the Fed and the ECB was one of monetary expansion through the purchase of large amounts of debt issued by countries. This practice had been used for decades in Japan, but it was not common in the arsenal of tools for an average official of another government.

Price increases are a monetary phenomenon, following the words of Milton Friedman, because if there are no changes in money flows, prices will be regulated through supply and demand. In the case of oil, it is something more complex, like almost everything in life. It will depend on how much the tap of countries opens and closes, meaning the cartelization of production. That is why, in the face of an expansive policy of the money supply, China needed to have allies to turn to when upward price fluctuations were accentuated due to manipulation of supply.

In summary, if, in addition to having more money in the system, the ability of OPEC to limit production is added, it is crucial to have one or more friends within that club, and even more so if they owe you a lot of money in loans.

According to Reuters, Venezuela exported 400 thousand barrels of oil to China in 2022. Some are intended for debt repayment, and others are paid for, but the proportion of each part is not specified, being one of the many secrets that the Revolution and China keep.

With doors closed in the US markets due to their poor relationship, the de facto embargo of CITGO, and the decrease in oil production due to corruption, Venezuela will hardly be able to fulfill its commitments and will have to repeatedly resort to loans from the Xi Jinping government to survive.

The exact price per barrel that would balance the nation's budget is unknown. According to information also published by Reuters, Venezuela presents the following data:

Oil revenues, equivalent to about $8.2 billion according to government calculations, will cover health, education, and public sector salaries, the proposal estimates.

The total budget amounts to about $13.56 billion.

This year, oil revenues financed approximately 29% of the budget, around $1.3 billion until August.

The proposal does not establish government estimates for economic growth, inflation, or the exchange rate for next year. The central bank has not published economic data since late 2019.

My bet, to conclude this article is that China will manage the timing as it has done for decades to maintain a relationship with Venezuela based on the country's need for fresh money on a recurrent basis. That is why in the last 10 years, there have been no less than 6 presidential summits between the two countries, whose agenda is opaque mainly or at least poorly publicized.

However, the day will come when China will want to see its money flow back, and that is when I understand that pragmatism will outweigh affinity, and the Chinese government will negotiate with some opposing political force that can snatch power from Chavismo, increasing the slim likelihood of being able to at least partially repay everything that has been publicly and almost secretly borrowed from China.

Bonus: Here’s a video that condenses much of what I’ve talked about in this article.

This text is a summary of the article which is longer, and written in technical language.