The Crossroad of the Venezuelan Oil Industry

What are the implications for the world when Venezuela became the country with the biggest oil reserves, and the possibility that those reserves will never exploited.

In 2009, when Hugo Chavez was still the president of Venezuela, he proudly announced on national television that the country had surpassed Saudi Arabia as the nation with the largest oil reserves in the world. It was a grand announcement that suggested a prosperous future for a country already rich in resources.

The Orinoco Oil Belt in the south of Venezuela, located just below the riverbed with the same name, is equivalent to 42 times the city extension of Los Angeles or the size of the whole of Croatia. It contains some 235 billion barrels of extra-heavy oil (between 4 and 16 API grades), which are challenging to extract but have become reachable through advanced technology. Despite the high cost of refining, the price of a barrel in the market (which averaged around US$85 between 2010-2012) made such problems of little importance.

Although fossil fuels still play a fundamental role in the geopolitical and economic board of international relations, regional accommodation, and even a country's creditworthiness, the current ranking of oil reserves shows that Venezuela's Orinoco Oil Belt is a significant player. Chavez and his XXI Century Socialism project had won the lottery overnight.

A Socialist approach to oil

Exacerbated nationalism eventually took control of the oil company, a couple of years before the industry resisted being dominated by nationalist, socialist, and anti-elitist approaches. The intervention was based on the thesis that oil had been a tool of the rich and had served only a few, increasing class differences.

Oil activity requires a high degree of reinvestment of the capital obtained, including amortizing equipment and acquiring new devices. However, the government chose to distribute the funds from oil sales into social programs called “missions.”

While these programs addressed some social injustice and inequality in Venezuela, they simultaneously represented a source of corruption. They were used as political propaganda to strengthen the influence of the XXI Century Revolution among sectors with fewer resources.

A perverse process was beginning. Disinvestment in exploration, prospecting, extraction, and refining occurred, and the state oil company was losing a significant portion of the talent generated after decades of training.

Simultaneously, the general deterioration of the country's business capacity was reducing the ability to produce in other areas of the economy. The number of tourists fell, and industries such as textiles, food, and auto parts closed their doors and, in some cases, relocated their plants abroad.

As a result, oil became the largest source of income and increased in weight in the overall export revenue, giving the government more power.

Carbon Footprint and Global Warming

Today, in 2020, these two concepts are commonly used by institutions and their leaders, and by the media, even by girls as young as 15 years old, who are demanding in front of their country’s parliament in the “Skolstrejk för klimatet.”

If we consult Google Trends, we will see that it was in 2006 when the term ”Global Warming” became popular, the year Al Gore made public the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” showing clearly the direct relationship between carbon emissions and rising temperatures.

Even though the UN had been working since the 1990s on conferences such as the Kyoto Protocol, the problem did not reach the rank of a global threat until mid-2007. In 2015 the Paris Climate Agreement was signed, whose first objective is to achieve carbon neutrality through the transition to new forms of energy. Oil-producing countries are still digesting the idea.

💡 Paris Agreement’s central aim is “to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius”.

The main instrument to achieve this is to make the planet carbon neutral by 2030, that is, making greenhouse gas (GHG) volume equal to the planet's absorption.

The interesting point about this agreement is that it does not speak of ‘stopping using fossil fuels’ but of being ‘neutral,’ so it leaves the window open for new technologies (carbon sequestration perhaps) to continue with the business as usual and still meet the goals of the agreement.

Nowadays, the main ways to deal with emissions are either by reducing them or through the carbon offset market. Assuming that carbon sequestration tools won’t be developed, these two visions will have different implications for the future of Venezuela’s oil activity.

Stranded Asset

In November 2020, the Financial Times published an article that raised the possibility of Venezuela using its reserves amid the new energy scenario.

Pundits were consulted for writing the article, from which we can extract two opinions from people that know the scenario where the Venezuelan oil industry would have to play; first is Ricardo Hausman, former minister, who said:

“oil“will never be as important a driver of the economy again as it was”

And the second is Francisco Monaldi,

“You can already see companies are leaving Canada because of climate change. None of them will even consider Venezuela . . . there’s no doubt that there is a finite window for investment.”

Oil Production, thousand barrels daily [1965-2019]

When looking at Venezuela’s oil industry history, we notice that it has been deeply linked to politics, leading to continuous power struggles and sudden changes in its objectives.

Beyond the immense value of what is under the country’s earth, which raises doubt about its extraction’s impossibility, is to determine if it is realistic to think whether or not this situation will change soon.

The graph shows how Venezuela has lost production capacity as the socialist government remains in power. The oil industry has been decimated by corruption and mismanagement of available resources, leading to an abrupt fall in production and refining capacity.

Getting oil out of the ground requires large investments, so having an abundance of it is no guarantee that it can be exploited; this activity can only be carried out if the returns from extraction are positive.

If a country like Venezuela, where oil belongs to the state and whose government lacks any credibility concerning the capacity to repay its debts, most probably won’t have access to the necessary capital to invest in exploration, prospecting, and extraction.

Additionally, oil prices are expected to fall (or at least remain relatively low) due to a clear mandate from large consumer countries to transcend the use of fossil fuels. Even in those without government pressure, consumers opt for new forms of energy, raising the question of whether or not it is worth making large investments to keep the oil flowing in.

The only window that remains open (which represents a zero-sum game for the planet) is that the transition to greener options could be slowed down or even discouraged by developing countries’ governments. The reason for this is simple; the profitability of oil use is much higher than that of renewable energy.

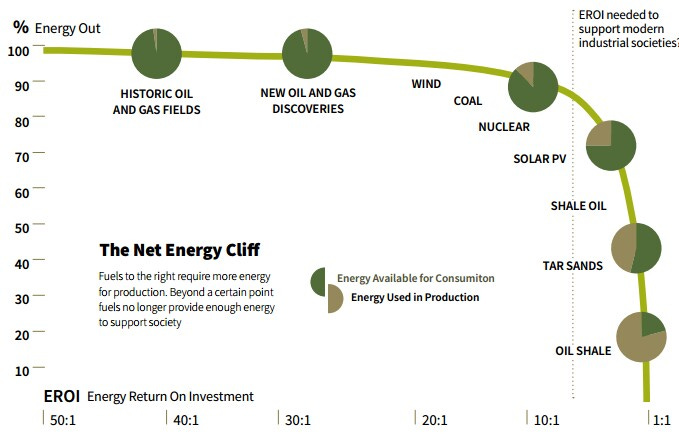

Regarding Return on Energy per unit invested (EROEI), fossil fuels have no competition, except nuclear energy.

Source: http://roperld.com/science/minerals/EROEIFossilFuels.htm

Potential Future Scenarios

Source: FT

Venezuela currently has limited options, despite the conditions, and the possibilities of developing them will diminish as time passes. These are:

Opening to international capital

Dismantling is the system in which the government regulates all economic activities, allowing the free circulation of capital. Suppose this measure is accompanied by an aggressive fiscal measures package, with exemptions for those who create jobs and invest in gross fixed capital formation. In that case, it can bring about domestic economic reactivation.

This can boost the development of the domestic economy and production for export. Venezuela could be host to companies searching for cheap energy for their industrial activities or hosting of virtual infrastructure (crypto-currency, servers in general).

This scenario includes the privatization of the industry or public-private co-ownership, promoting confidence in the producing company.

Playing with ‘neutrality’ as a concept

The country has the potential to propose schemes to raise funds for the fight against climate change. It could generate income for the non-pollution that its resources could cause by allocating enormous amounts of resources to developing other forms of energy, such as hydroelectric power, and developing a business network that promotes a green economy.

Although the carbon credit market is currently only worth 215 billion dollars, this is a valid scheme considering how monetary policy is managed in large economies. It is common to see Central Banks (or the Federal Reserve) multiply their balance sheets to extraordinary magnitudes to energize the economy in difficult times. If this concept is extrapolated to the "health of the planet," countries with high productivity can finance those with lower productivity to keep them away from fossil fuel production.

Although it may seem distant, as the UN Secretary-General mentioned, the "central objective" for next year (2021) will be to build a global coalition around the need to reduce emissions to net zero.

There are at least two concepts accepted as valid in this analysis: first, that Venezuela has systematically destroyed its capacity to produce oil, and second, that the weight of oil in geopolitics is decreasing and will continue to decline as new generations of leaders take the reins of their respective countries.

—

Juan Carlos Golindano S.

Dec. 6th, 2020